What follows is Christina Torres’s article on teaching middle school in Hawaii and a response from my friend, Maritza Gerbrandy-Dahl. Like Torres, Maritza teaches middle school. And like Torres, Maritza often doesn’t know if she can continue another year.

You will laugh, sigh and bleed a little as you read Gerbandy-Dahl’s response.

Teaching Saves My Life Every Single Day

When I wake up, my arms are wound around me — tight— protecting me from something I can’t name. (…) I never know how a morning is going to hit. Most days, I awake feeling excited and eager to hop on my bike for the five-minute commute to the beautiful school in Honolulu, Hawaii where I teach middle school English. I am very, very lucky.

Some mornings, though, I am fighting my way out of a deep, dark hole.

I’ve been managing anxiety (and, at times, its cousin, depression) since I was a kid. (…) Yet, to my surprise, I’ve found one of the most effective remedies in the very place the darkness tries to coax me away from some mornings: at school, with the 96 kids I see at work each day.

(…)

The first step is getting out of bed. I place my hands on the mattress to push up and — “Why bother? You can’t do this. You’re not going to be able to handle what’s out there.” The “what” is never clear — it’s everything. It’s light and sound; other people and life itself.

===

Normally, the traits you associate with “introvert” and “anxiety” don’t overlap with “middle school English teacher.” Still, for most of my adult life, that’s the paradox I live. Every day, I see anywhere from 48 to 96 eighth graders, inviting them to write, read, think, and laugh with me. My work allows me to question, engage, and love small humans. They fill me with amusement, encouragement, and awe.

It’s incredibly rewarding, but immensely tiring. The double-edged sword of teaching is the continued (and, often, draining) presence of people throughout your workday. Some of us aptly describe it as having to be “on” — teaching requires a tremendous sense of presence, all while knowing each interaction with a kid can change the culture of your classroom for a day — or more. The stakes are high.

When I first started teaching, the pressure of being “on,” of having to “perform” was tiring. I would end each day emotionally exhausted, barely able to comprehend doing this for the rest of the week, much less year.

After a few years, though, I realized teaching isn’t a performance at all — it’s a relationship. My kids didn’t need me to entertain them. They needed me to enter into kinship with them, to care about them and, at the same time, allow them to care about me. And in this way, teaching saves my life every single day.

(…)

Most kids just want to be loved and love in return. I have yet to find a group of kids who didn’t want to, in some way, have a good time, care about, and enjoy the company of their teachers and peers. Even when, for whatever reason, it is hard for them to trust and express that, showing a student that I care about them has always gained the care and companionship of that kid.

In this way, my students remind me that the voice that says I am unworthy of love or that life is not worthwhile is lying. Of course, I am blessed to also have family and friends who would remind me of this if I needed it, but the power of doing work that is truly based on creating kinship has a magic of its own.

(…)

In entering into kinship with my students, I don’t just see the best and seek the best for them; I let them show me the best of myself too. The more I teach, the more I realize it’s one of the best expressions of love I could ask for — the hope, joy, and magic of kids calls me back from the darkness.

Even when life feels hopeless, there is so much unfailing light in the world — especially in children. And that light is often at the end of the dark tunnel of my own mind, guiding me back home to myself.

Maritza Gerbandy-Dahl response to the above article:

Everything she said in this, I thought dozens of times last week.

My school is busting at the seams.

The kids were so agitated last week that even my best students appeared exhausted and depressed. So I did the ‘kinship’ building this woman talked about, and set aside Valentine’s Day to create extended metaphors on love.

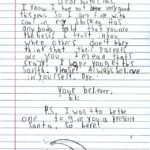

Even the nastiest players got into it, and what was perhaps the most touching was how they needed to have me see what they had produced. When one wrote: “Love is like my penis, it’s hard sometimes,” I laughed and laughed and told him that was incredibly clever, but for reasons I think he understood, that one wasn’t going on the board. He immediately wrote another that was utterly beautiful: “Love is the moon, sometimes full and shining in a dark sky, sometimes extinguished.” And I kissed him on his forehead, and he blushed – this boy who is the bane of every other teacher’s existence – and he said, “You know Ms. Dahl, I really do love you.” And I smiled and said, “I know.”

This is the stuff you read about in Harlequin romances, not real life, yet there it is. I got Valentine Day cards they made themselves (because I’d preached at them about how commercialized it had become, and how we made our own when we were young). And kids were running out of foods class to bring me a chocolate cupcake or a blueberry muffin.

One girl who is very angry, loud. She told the class she slammed a door on her sister’s fingers and amputated a finger. I took the time to tell her that her ‘spirit’ was loud and exuberant and that she had a heart of gold, and watched her all week as she responded to that one simple sentence. And she came up to hug me and said, “I’m exuberant, Ms. Dahl. No one ever told me that. But, you know, I am.” Every day I wondered how I was going to survive another day, and in the end, it was one gift after another.

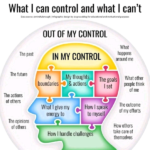

Two of the most difficult girls in the school began one period telling me they had actually been listening to things I had said, and they got into a discussion about what love really was. They asked me if love was a good thing, and I said, not always, because it’s often just a feeling that passes. And Ashley said, “Yeah, it can turn, like, into hate just like that.” And I said, “Isn’t that weird?”

I told her I thought love was overrated, and that the real ingredient in a good life is empathy. I explained what that was. And she said, “Yeah, you’re the only teacher that kinda gets it when we say, ‘Get the fuck out of my life,’ and you don’t get mad.” Whereupon she talked about how her mother ultimately divorced her father, how messed up he was, how mad she was at her mom, how she hated but loved her dad, and how, in the end, she knew her mother had taught her something important. I asked what that was, and she said, “It’s for women, don’t take crap from any guy,” and I nodded.

And at the end of the week, when three of our teachers were emailing about how many kids are coming tardy to class, and I looked, I realized not one kid, not one, had been tardy to my class.

So I wrestle with this, because, exhausted as I am, it keeps me alive and awake.